Beavers in Winter – A Report from the Field

It’s Transition Time for Beavers in the Deschutes River Basin - Winter 2020

A Report from the Field

Beavers around Central Oregon spend much of their lives moving mysteriously up and down the Deschutes River unseen. Even on hot summer days as we float just past their hidden “bank dens”, humans are more likely to notice the 20-plus other species who make their homes in ecologically rich “beaver waters,” such as otters, mink, and fish, than to notice the shy beaver. It’s why Beaver Works Oregon is working to better understand beaver presence along the Deschutes and the obstacles they face in our riverine landscapes. With the transition from fall to winter, the changes are many and can be an especially tricky time for a beaver’s survival. Here’s what we’re seeing as beavers adapt to winter.

Food availability and caching

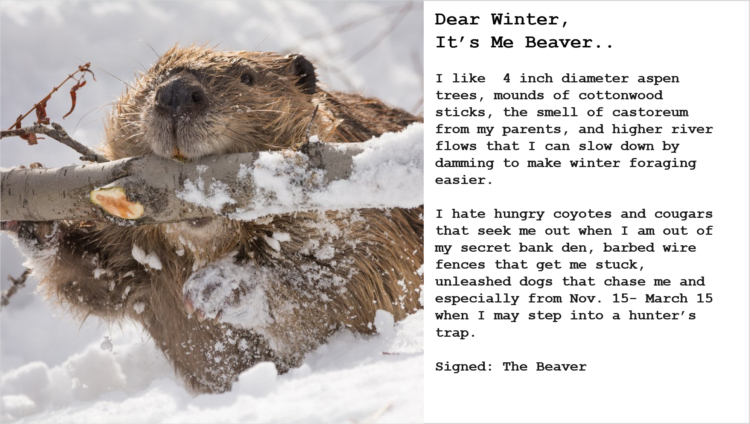

As the season changes over to winter, food sources like green vegetation dry up, forcing beavers to forage farther inland on trees like willow, cottonwood, aspen, alders, or backyard maples. These preferred trees have nutrients that conifer trees, like pines and juniper, do not. Caching food stores is a primary beaver activity in fall preparing for winter. (Over one year’s time, a single beaver can require 500-1000 lbs of food, or as much as one acre of grasses and woody vegetation per beaver, annually.) In recent monitoring of a Beaver Works designated “Riverhood” in Redmond, field technician Pamela Adams observed “It was like a cottonwood rave, the beavers chewed down the 30 cottonwood tree sticks I planted. At least I caged one tree. It was certainly a Thanksgiving feast for these two adults, a yearling, and this year’s kit.” Adams learned from her trail camera that this family chewed down every stick, and debarked them from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. They were very polite with the caged tree — even though they did sample a tiny branch that stuck out. “It’s time to fence your vulnerable trees by wrapping with wire mesh.” said Adams. View the Redmond Riverhood and Cottonwood Plantings on Youtube The Beaver Response Team is also out and about learning the other obstacles beavers face in winter besides getting enough food stored in their dens.

Deschutes River flow increases require adaptations

- Moving Time. As Deschutes River high-water marks can fluctuate 2 to 3 feet in the fall, out of necessity beavers may relocate their “homes” to different locations from the low-water marks of summer. Since early October, the Deschutes has been rushing so much faster that it’s hard to believe the beavers can swim upstream at all. This movement to new digs also may create beaver territorial conflicts, as each colony needs a certain amount of territory between other beaver colonies.

- Territorial Responses. Beaver Response Team trail camera footage has even picked up some up-close (and a bit personal) behavior of a beaver starting a scent mound — something they usually do in the spring, not fall, per biologists. These “mounds of stink” are made up of river mud, leaves, sticks, and daily deposits of beaver bodily secretions. Beavers actually sequence plant chemicals (allelochemicals) and store in their castor sacs, urinary, and anal glands which get released as chemical messages. Like a social media post, these scent mounds communicate everything from the identity of the individual, group, or sex, sexual readiness, social status, health, location-territorial ownership.

- Dam Building. The best-known beaver behavior is that beavers build dams. Beaver dams on the stem of the Deschutes River are rare, but there are some back-channel dams that beavers make to slow and then hold the water for them to forage safely. Those webbed hind feet make them great swimmers — even the kits — and they can hold their breath for 15 minutes, so water is their preferred, safer path rather than becoming a “walking hot dog” for predators on land when they bring their groceries back to the den.

- Extended Foraging via Beaver Built Tunnels. Another recent observation around a Middle Deschutes neighborhood is an impressive beaver food harvest area some distance from the watery safety of the river. Within this “beaver willow farm” area grow a half-dozen old-growth willows and alders, perfectly pruned seemingly overnight. Further inspection revealed that the beavers had dug “a run” with holes and tunnels to the river for ease in hauling their bounty to their underwater bank burrow. By the time the Beaver Response Team found this new spot and set up trail cameras, the beavers had already gotten in and out in one night of foraging. The trail camera only picked up one image over the next week: a curious bobcat looking into the empty beaver getaway tunnel.

Human predation one of the largest obstacles

The Beaver Response Team rejoices in bearing witness to beavers’ heroic journey here in Central Oregon. We are learning how adaptable beaver are despite near extinction a couple of centuries ago — caused not by natural predators or habitat hurdles, but by Euro-American trappers pursuing a Fur Desert policy. Unfortunately, Oregon state’s management of beaver – as both “fur-bearer” and “predator” species – is one of the largest obstacles to beaver populations today. In fact, just as beaver mating season begins, Oregon has opened its fur-bearer trapping season – November 15 through March 15 – creating further pressures for beaver families in winter.

Removing obstacles where possible

The Beaver Response Team works to remove obstacles to beaver survival, supporting coexistence when conflicts arise, through exclusion fencing, flow device installation, and other tools to mitigate beaver impacts that may challenge human interests along the Deschutes.

This winter, we invite you to join us in this journey – subscribe to Beaver Works Youtube channel, follow Beaver Works Oregon on Facebook or Instagram, join our mailing list or donate to this work.